The Ordering Service¶

Audience: Architects, ordering service admins, channel creators

This topic serves as a conceptual introduction to the concept of ordering, how orderers interact with peers, the role they play in a transaction flow, and an overview of the currently available implementations of the ordering service, with a particular focus on the Raft ordering service implementation.

What is ordering?¶

Many distributed blockchains, such as Ethereum and Bitcoin, are not permissioned, which means that any node can participate in the consensus process, wherein transactions are ordered and bundled into blocks. Because of this fact, these systems rely on probabilistic consensus algorithms which eventually guarantee ledger consistency to a high degree of probability, but which are still vulnerable to divergent ledgers (also known as a ledger “fork”), where different participants in the network have a different view of the accepted order of transactions.

Hyperledger Fabric works differently. It features a node called an orderer (it’s also known as an “ordering node”) that does this transaction ordering, which along with other orderer nodes forms an ordering service. Because Fabric’s design relies on deterministic consensus algorithms, any block validated by the peer is guaranteed to be final and correct. Ledgers cannot fork the way they do in many other distributed and permissionless blockchain networks.

In addition to promoting finality, separating the endorsement of chaincode execution (which happens at the peers) from ordering gives Fabric advantages in performance and scalability, eliminating bottlenecks which can occur when execution and ordering are performed by the same nodes.

Orderer nodes and channel configuration¶

In addition to their ordering role, orderers also maintain the list of organizations that are allowed to create channels. This list of organizations is known as the “consortium”, and the list itself is kept in the configuration of the “orderer system channel” (also known as the “ordering system channel”). By default, this list, and the channel it lives on, can only be edited by the orderer admin. Note that it is possible for an ordering service to hold several of these lists, which makes the consortium a vehicle for Fabric multi-tenancy.

Orderers also enforce basic access control for channels, restricting who can read and write data to them, and who can configure them. Remember that who is authorized to modify a configuration element in a channel is subject to the policies that the relevant administrators set when they created the consortium or the channel. Configuration transactions are processed by the orderer, as it needs to know the current set of policies to execute its basic form of access control. In this case, the orderer processes the configuration update to make sure that the requestor has the proper administrative rights. If so, the orderer validates the update request against the existing configuration, generates a new configuration transaction, and packages it into a block that is relayed to all peers on the channel. The peers then processs the configuration transactions in order to verify that the modifications approved by the orderer do indeed satisfy the policies defined in the channel.

Orderer nodes and Identity¶

Everything that interacts with a blockchain network, including peers, applications, admins, and orderers, acquires their organizational identity from their digital certificate and their Membership Service Provider (MSP) definition.

For more information about identities and MSPs, check out our documentation on Identity and Membership.

Just like peers, ordering nodes belong to an organization. And similar to peers, a separate Certificate Authority (CA) should be used for each organization. Whether this CA will function as the root CA, or whether you choose to deploy a root CA and then intermediate CAs associated with that root CA, is up to you.

Orderers and the transaction flow¶

Phase one: Proposal¶

We’ve seen from our topic on Peers that they form the basis for a blockchain network, hosting ledgers, which can be queried and updated by applications through smart contracts.

Specifically, applications that want to update the ledger are involved in a process with three phases that ensures all of the peers in a blockchain network keep their ledgers consistent with each other.

In the first phase, a client application sends a transaction proposal to a subset of peers that will invoke a smart contract to produce a proposed ledger update and then endorse the results. The endorsing peers do not apply the proposed update to their copy of the ledger at this time. Instead, the endorsing peers return a proposal response to the client application. The endorsed transaction proposals will ultimately be ordered into blocks in phase two, and then distributed to all peers for final validation and commit in phase three.

For an in-depth look at the first phase, refer back to the Peers topic.

Phase two: Ordering and packaging transactions into blocks¶

After the completion of the first phase of a transaction, a client application has received an endorsed transaction proposal response from a set of peers. It’s now time for the second phase of a transaction.

In this phase, application clients submit transactions containing endorsed transaction proposal responses to an ordering service node. The ordering service creates blocks of transactions which will ultimately be distributed to all peers on the channel for final validation and commit in phase three.

Ordering service nodes receive transactions from many different application clients concurrently. These ordering service nodes work together to collectively form the ordering service. Its job is to arrange batches of submitted transactions into a well-defined sequence and package them into blocks. These blocks will become the blocks of the blockchain!

The number of transactions in a block depends on channel configuration

parameters related to the desired size and maximum elapsed duration for a

block (BatchSize and BatchTimeout parameters, to be exact). The blocks are

then saved to the orderer’s ledger and distributed to all peers that have joined

the channel. If a peer happens to be down at this time, or joins the channel

later, it will receive the blocks after reconnecting to an ordering service

node, or by gossiping with another peer. We’ll see how this block is processed

by peers in the third phase.

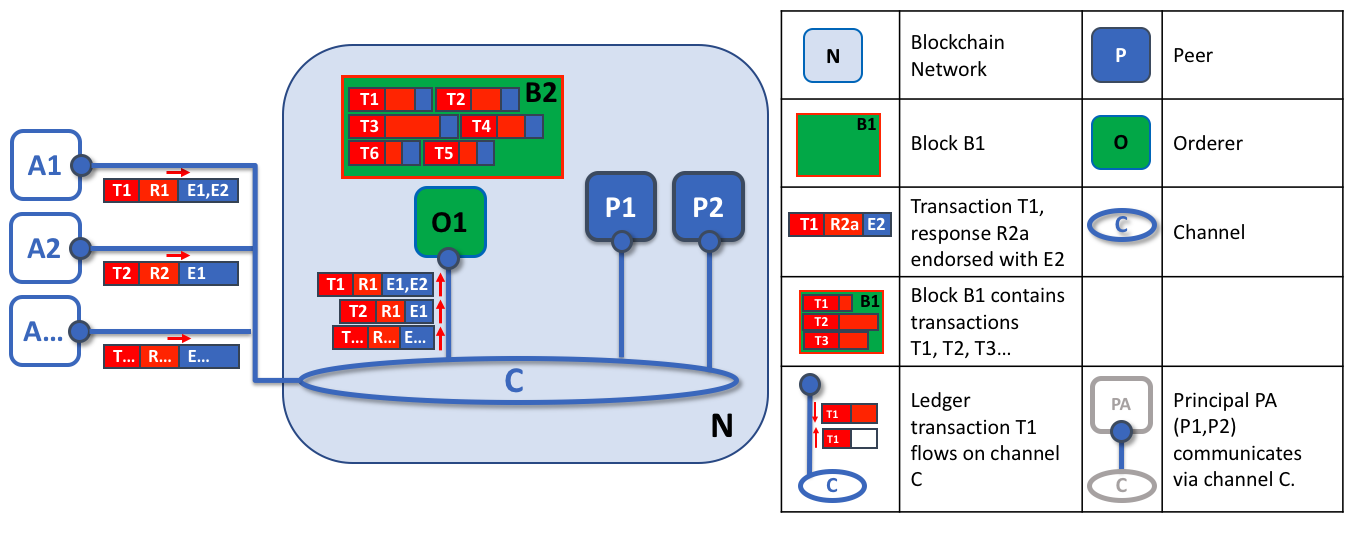

The first role of an ordering node is to package proposed ledger updates. In this example, application A1 sends a transaction T1 endorsed by E1 and E2 to the orderer O1. In parallel, Application A2 sends transaction T2 endorsed by E1 to the orderer O1. O1 packages transaction T1 from application A1 and transaction T2 from application A2 together with other transactions from other applications in the network into block B2. We can see that in B2, the transaction order is T1,T2,T3,T4,T6,T5 – which may not be the order in which these transactions arrived at the orderer! (This example shows a very simplified ordering service configuration with only one ordering node.)

It’s worth noting that the sequencing of transactions in a block is not necessarily the same as the order received by the ordering service, since there can be multiple ordering service nodes that receive transactions at approximately the same time. What’s important is that the ordering service puts the transactions into a strict order, and peers will use this order when validating and committing transactions.

This strict ordering of transactions within blocks makes Hyperledger Fabric a little different from other blockchains where the same transaction can be packaged into multiple different blocks that compete to form a chain. In Hyperledger Fabric, the blocks generated by the ordering service are final. Once a transaction has been written to a block, its position in the ledger is immutably assured. As we said earlier, Hyperledger Fabric’s finality means that there are no ledger forks — validated transactions will never be reverted or dropped.

We can also see that, whereas peers execute smart contracts and process transactions, orderers most definitely do not. Every authorized transaction that arrives at an orderer is mechanically packaged in a block — the orderer makes no judgement as to the content of a transaction (except for channel configuration transactions, as mentioned earlier).

At the end of phase two, we see that orderers have been responsible for the simple but vital processes of collecting proposed transaction updates, ordering them, and packaging them into blocks, ready for distribution.

Phase three: Validation and commit¶

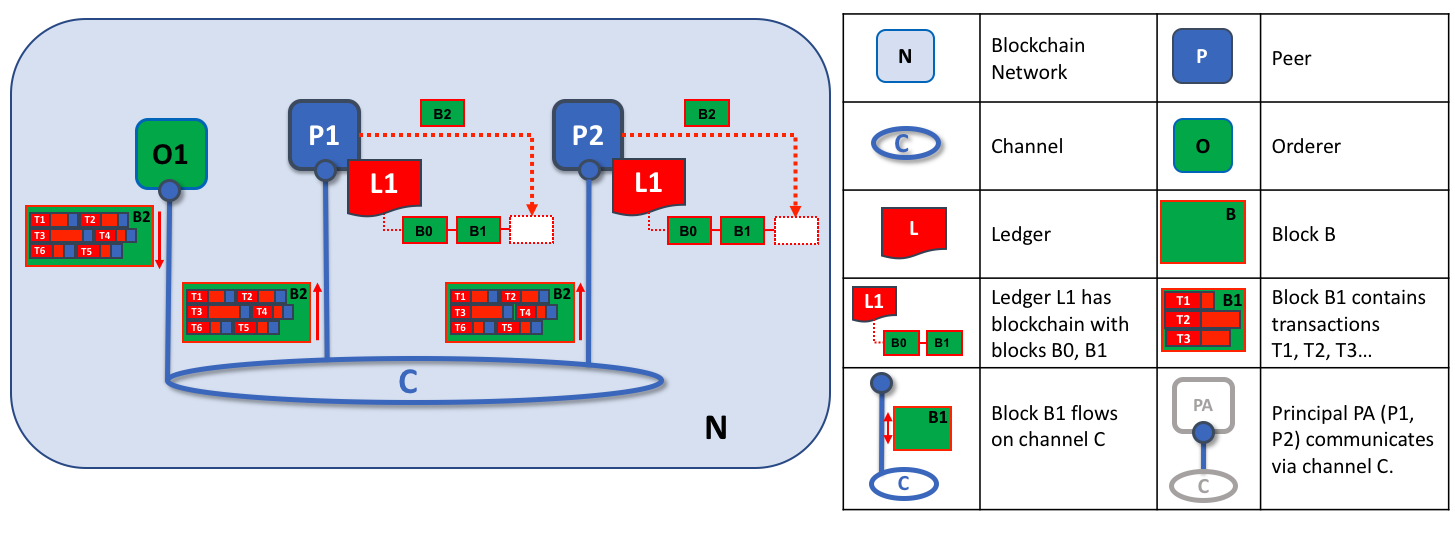

The third phase of the transaction workflow involves the distribution and subsequent validation of blocks from the orderer to the peers, where they can be committed to the ledger.

Phase 3 begins with the orderer distributing blocks to all peers connected to it. It’s also worth noting that not every peer needs to be connected to an orderer — peers can cascade blocks to other peers using the gossip protocol.

Each peer will validate distributed blocks independently, but in a deterministic fashion, ensuring that ledgers remain consistent. Specifically, each peer in the channel will validate each transaction in the block to ensure it has been endorsed by the required organization’s peers, that its endorsements match, and that it hasn’t become invalidated by other recently committed transactions which may have been in-flight when the transaction was originally endorsed. Invalidated transactions are still retained in the immutable block created by the orderer, but they are marked as invalid by the peer and do not update the ledger’s state.

The second role of an ordering node is to distribute blocks to peers. In this example, orderer O1 distributes block B2 to peer P1 and peer P2. Peer P1 processes block B2, resulting in a new block being added to ledger L1 on P1. In parallel, peer P2 processes block B2, resulting in a new block being added to ledger L1 on P2. Once this process is complete, the ledger L1 has been consistently updated on peers P1 and P2, and each may inform connected applications that the transaction has been processed.

In summary, phase three sees the blocks generated by the ordering service applied consistently to the ledger. The strict ordering of transactions into blocks allows each peer to validate that transaction updates are consistently applied across the blockchain network.

For a deeper look at phase 3, refer back to the Peers topic.

Ordering service implementations¶

While every ordering service currently available handles transactions and configuration updates the same way, there are nevertheless several different implementations for achieving consensus on the strict ordering of transactions between ordering service nodes.

For information about how to stand up an ordering node (regardless of the implementation the node will be used in), check out our documentation on standing up an ordering node.

Raft

New as of v1.4.1, Raft is a crash fault tolerant (CFT) ordering service based on an implementation of Raft protocol in

etcd. Raft follows a “leader and follower” model, where a leader node is elected (per channel) and its decisions are replicated by the followers. Raft ordering services should be easier to set up and manage than Kafka-based ordering services, and their design allows different organizations to contribute nodes to a distributed ordering service.

Kafka

Similar to Raft-based ordering, Apache Kafka is a CFT implementation that uses a “leader and follower” node configuration. Kafka utilizes a ZooKeeper ensemble for management purposes. The Kafka based ordering service has been available since Fabric v1.0, but many users may find the additional administrative overhead of managing a Kafka cluster intimidating or undesirable.

Solo

The Solo implementation of the ordering service is intended for test only and consists only of a single ordering node. It has been deprecated and may be removed entirely in a future release. Existing users of Solo should move to a single node Raft network for equivalent function.

Raft¶

For information on how to configure a Raft ordering service, check out our documentation on configuring a Raft ordering service.

The go-to ordering service choice for production networks, the Fabric implementation of the established Raft protocol uses a “leader and follower” model, in which a leader is dynamically elected among the ordering nodes in a channel (this collection of nodes is known as the “consenter set”), and that leader replicates messages to the follower nodes. Because the system can sustain the loss of nodes, including leader nodes, as long as there is a majority of ordering nodes (what’s known as a “quorum”) remaining, Raft is said to be “crash fault tolerant” (CFT). In other words, if there are three nodes in a channel, it can withstand the loss of one node (leaving two remaining). If you have five nodes in a channel, you can lose two nodes (leaving three remaining nodes).

From the perspective of the service they provide to a network or a channel, Raft and the existing Kafka-based ordering service (which we’ll talk about later) are similar. They’re both CFT ordering services using the leader and follower design. If you are an application developer, smart contract developer, or peer administrator, you will not notice a functional difference between an ordering service based on Raft versus Kafka. However, there are a few major differences worth considering, especially if you intend to manage an ordering service:

- Raft is easier to set up. Although Kafka has scores of admirers, even those admirers will (usually) admit that deploying a Kafka cluster and its ZooKeeper ensemble can be tricky, requiring a high level of expertise in Kafka infrastructure and settings. Additionally, there are many more components to manage with Kafka than with Raft, which means that there are more places where things can go wrong. And Kafka has its own versions, which must be coordinated with your orderers. With Raft, everything is embedded into your ordering node.

- Kafka and Zookeeper are not designed to be run across large networks. They are designed to be CFT but should be run in a tight group of hosts. This means that practically speaking you need to have one organization run the Kafka cluster. Given that, having ordering nodes run by different organizations when using Kafka (which Fabric supports) doesn’t give you much in terms of decentralization because the nodes will all go to the same Kafka cluster which is under the control of a single organization. With Raft, each organization can have its own ordering nodes, participating in the ordering service, which leads to a more decentralized system.

- Raft is supported natively. While Kafka-based ordering services are currently compatible with Fabric, users are required to get the requisite images and learn how to use Kafka and ZooKeeper on their own. Likewise, support for Kafka-related issues is handled through Apache, the open-source developer of Kafka, not Hyperledger Fabric. The Fabric Raft implementation, on the other hand, has been developed and will be supported within the Fabric developer community and its support apparatus.

- Where Kafka uses a pool of servers (called “Kafka brokers”) and the admin of the orderer organization specifies how many nodes they want to use on a particular channel, Raft allows the users to specify which ordering nodes will be deployed to which channel. In this way, peer organizations can make sure that, if they also own an orderer, this node will be made a part of a ordering service of that channel, rather than trusting and depending on a central admin to manage the Kafka nodes.

- Raft is the first step toward Fabric’s development of a byzantine fault tolerant (BFT) ordering service. As we’ll see, some decisions in the development of Raft were driven by this. If you are interested in BFT, learning how to use Raft should ease the transition.

Note: Similar to Solo and Kafka, a Raft ordering service can lose transactions after acknowledgement of receipt has been sent to a client. For example, if the leader crashes at approximately the same time as a follower provides acknowledgement of receipt. Therefore, application clients should listen on peers for transaction commit events regardless (to check for transaction validity), but extra care should be taken to ensure that the client also gracefully tolerates a timeout in which the transaction does not get committed in a configured timeframe. Depending on the application, it may be desirable to resubmit the transaction or collect a new set of endorsements upon such a timeout.

Raft concepts¶

While Raft offers many of the same features as Kafka — albeit in a simpler and easier-to-use package — it functions substantially different under the covers from Kafka and introduces a number of new concepts, or twists on existing concepts, to Fabric.

Log entry. The primary unit of work in a Raft ordering service is a “log entry”, with the full sequence of such entries known as the “log”. We consider the log consistent if a majority (a quorum, in other words) of members agree on the entries and their order, making the logs on the various orderers replicated.

Consenter set. The ordering nodes actively participating in the consensus mechanism for a given channel and receiving replicated logs for the channel. This can be all of the nodes available (either in a single cluster or in multiple clusters contributing to the system channel), or a subset of those nodes.

Finite-State Machine (FSM). Every ordering node in Raft has an FSM and collectively they’re used to ensure that the sequence of logs in the various ordering nodes is deterministic (written in the same sequence).

Quorum. Describes the minimum number of consenters that need to affirm a proposal so that transactions can be ordered. For every consenter set, this is a majority of nodes. In a cluster with five nodes, three must be available for there to be a quorum. If a quorum of nodes is unavailable for any reason, the ordering service cluster becomes unavailable for both read and write operations on the channel, and no new logs can be committed.

Leader. This is not a new concept — Kafka also uses leaders, as we’ve said — but it’s critical to understand that at any given time, a channel’s consenter set elects a single node to be the leader (we’ll describe how this happens in Raft later). The leader is responsible for ingesting new log entries, replicating them to follower ordering nodes, and managing when an entry is considered committed. This is not a special type of orderer. It is only a role that an orderer may have at certain times, and then not others, as circumstances determine.

Follower. Again, not a new concept, but what’s critical to understand about followers is that the followers receive the logs from the leader and replicate them deterministically, ensuring that logs remain consistent. As we’ll see in our section on leader election, the followers also receive “heartbeat” messages from the leader. In the event that the leader stops sending those message for a configurable amount of time, the followers will initiate a leader election and one of them will be elected the new leader.

Raft in a transaction flow¶

Every channel runs on a separate instance of the Raft protocol, which allows each instance to elect a different leader. This configuration also allows further decentralization of the service in use cases where clusters are made up of ordering nodes controlled by different organizations. While all Raft nodes must be part of the system channel, they do not necessarily have to be part of all application channels. Channel creators (and channel admins) have the ability to pick a subset of the available orderers and to add or remove ordering nodes as needed (as long as only a single node is added or removed at a time).

While this configuration creates more overhead in the form of redundant heartbeat messages and goroutines, it lays necessary groundwork for BFT.

In Raft, transactions (in the form of proposals or configuration updates) are automatically routed by the ordering node that receives the transaction to the current leader of that channel. This means that peers and applications do not need to know who the leader node is at any particular time. Only the ordering nodes need to know.

When the orderer validation checks have been completed, the transactions are ordered, packaged into blocks, consented on, and distributed, as described in phase two of our transaction flow.

Architectural notes¶

How leader election works in Raft¶

Although the process of electing a leader happens within the orderer’s internal processes, it’s worth noting how the process works.

Raft nodes are always in one of three states: follower, candidate, or leader. All nodes initially start out as a follower. In this state, they can accept log entries from a leader (if one has been elected), or cast votes for leader. If no log entries or heartbeats are received for a set amount of time (for example, five seconds), nodes self-promote to the candidate state. In the candidate state, nodes request votes from other nodes. If a candidate receives a quorum of votes, then it is promoted to a leader. The leader must accept new log entries and replicate them to the followers.

For a visual representation of how the leader election process works, check out The Secret Lives of Data.

Snapshots¶

If an ordering node goes down, how does it get the logs it missed when it is restarted?

While it’s possible to keep all logs indefinitely, in order to save disk space, Raft uses a process called “snapshotting”, in which users can define how many bytes of data will be kept in the log. This amount of data will conform to a certain number of blocks (which depends on the amount of data in the blocks. Note that only full blocks are stored in a snapshot).

For example, let’s say lagging replica R1 was just reconnected to the network.

Its latest block is 100. Leader L is at block 196, and is configured to

snapshot at amount of data that in this case represents 20 blocks. R1 would

therefore receive block 180 from L and then make a Deliver request for

blocks 101 to 180. Blocks 180 to 196 would then be replicated to R1

through the normal Raft protocol.

Kafka¶

The other crash fault tolerant ordering service supported by Fabric is an adaptation of a Kafka distributed streaming platform for use as a cluster of ordering nodes. You can read more about Kafka at the Apache Kafka Web site, but at a high level, Kafka uses the same conceptual “leader and follower” configuration used by Raft, in which transactions (which Kafka calls “messages”) are replicated from the leader node to the follower nodes. In the event the leader node goes down, one of the followers becomes the leader and ordering can continue, ensuring fault tolerance, just as with Raft.

The management of the Kafka cluster, including the coordination of tasks, cluster membership, access control, and controller election, among others, is handled by a ZooKeeper ensemble and its related APIs.

Kafka clusters and ZooKeeper ensembles are notoriously tricky to set up, so our documentation assumes a working knowledge of Kafka and ZooKeeper. If you decide to use Kafka without having this expertise, you should complete, at a minimum, the first six steps of the Kafka Quickstart guide before experimenting with the Kafka-based ordering service. You can also consult this sample configuration file for a brief explanation of the sensible defaults for Kafka and ZooKeeper.

To learn how to bring up a a Kafka-based ordering service, check out our documentation on Kafka.